The final published version of this report is now available from the Jisc website

TL;DR: This is a short report that looks at the potential in research and education of blockchain, the technology that underpins the Bitcoin virtual currency. Blockchain is currently at the peak of the hype cycle, so I spend a little time looking at how we can identify what’s realistic and avoid inflated expectations.

- Blockchain’s Bitcoin origins

The early history of Bitcoin is worth reflecting on:

Photo CC BY-SA Flickr user fstorr

- 2007: “Satoshi Nakamoto” allegedly begins development of the Bitcoin virtual currency

- 2009: Version 0.1 of Bitcoin is released on SourceForge, and the first transaction takes place

- 2010: Programmer buys pizza for 10,000BTC(now worth $39,454,600!)

- 2011: Silk Road “dark web” marketplace opens

- 2011: 25% of the 21 million possible Bitcoins now generated through mining operations

- More at http://historyofbitcoin.org/

Let’s unpick this a little – Bitcoins are generated from thin air by computers solving complex mathematical puzzles, a process known as “mining”, and there are a finite number of them. Not only this, but the puzzles get more complicated as more Bitcoins are mined.

Early Bitcoin mining could be done on a conventional PC, but it quickly became necessary to use very powerful hardware, and most Bitcoin mining operations these days involve hundreds or thousands of high performance servers in their own dedicated rooms or even buildings.

Blockchain is the underlying “distributed ledger” technology that powers Bitcoin. Audrey Watters has written this very helpful summary of blockchain on her Hack Education site:

- “The blockchain is a distributed database that provides an unalterable, (semi-)public record of digital transactions.

- Each block aggregates a timestamped batch of transactionsto be included in the ledger – or rather, in the blockchain.

- Each block is identified by a cryptographic signature.

- These blocks are all back-linked; that is, they refer to thesignature of the previous block in the chain, and that chaincan be traced all the way back to the very first block created.

- As such, the blockchain contains an un-editable record of all the transactions made.”

It’s worth reflecting for a moment on the key concepts here – an unalterable, semi-public database, that multiple untrusted parties can add entries to. Many early Bitcoin proponents saw it as an alternative to fiat currency controlled by governments and central banks. Some of these people were coming from a Libertarian background and generally suspicious of big government and central control, but others had genuinely nefarious intentions such as selling illegal goods online. We’ll see as the report goes on that whilst this might be where blockchain is coming from, its ultimate destination could be a very different place indeed, due to it having been embraced by those self-same governments and bankers – e.g. the UK government’s recent blockchain welfare payments trial.

We may never know who Satoshi Nakamoto really is or was, but making Bitcoin (and by extension blockchain) open source turned out to be a master stroke – a community quickly sprang up around the technology, working to improve it and fix bugs, and build products and services that integrated with it.

Dogecoin logo CC BY-SA Flickr user flyingblogspot

One characteristic of open source software is that people can “fork” it to create their own versions, or even base whole new products on it. What happened initially with Bitcoin was that a number of competing virtual currencies appeared, including Dogecoin, perhaps the world’s first joke currency.

A little further down the line people started to realise that the underlying technology could be useful in a wide range of applications. A notable example here is Namecoin, the first Bitcoin fork. Namecoin provides a decentralised alternative to key Internet infrastructure such as domain names and digital identifies

Whilst the blockchain concept started life as the underpinnings of a virtual currency, this interest in more general application quickly grew, leading to the development of Ethereum, a general purpose programmable blockchain system. Ethereum extends the blockchain concept to support “abstract decentralised transfer of value to a generalised state transition function, supporting any application” using a mechanism called smart contracts.

Smart contracts are small chunks of computer code written in a language that looks very similar to every web developer’s favourite (or bug bear?) JavaScript. This might sound intimidating but essentially what they do is automate the “if this, then do that…” elements of existing decision-making processes. For example: when the incoming funds have successfully cleared, record that the house ownership has transferred to the purchaser.

- Using blockchain in research & education

We’ll look at three key areas where blockchain could play a useful role, and some examples of projects and services that are exploring these use cases.

2.1 Credentialling

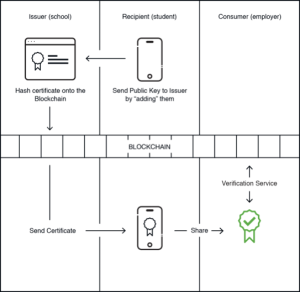

Blockcerts activity flow – from blockcerts.org, MIT License

The Blockcerts project from MIT and their collaborators has developed a blockchain based platform that lets institutions “build apps that issue and verify blockchain-based certificates for academic credentials, professional certifications, workforce development, and civic records”.

Blockcerts isn’t the only show in town, though. There are several other companies and projects exploring blockchain based approaches to issuing and verifying credentials, including startups such as Sweden’s GradBase and the UK’s APPII.

How could this work in practice? Let’s picture a few examples:

- Is Martin really a medical doctor? Should I let him perform brain surgery on me?

- Martin wants to transfer course to another university and take his academic credit with him

- Martin has been doing a work placement and his employer has some feedback to add

- Martin has lost his A Level / degree certificates…

2.2 Research provenance and reproducibility

The Blockchain for Science project is developing a manifesto that looks at how blockchain could “reduce overhead and accelerate the scientific process”, for example:

- Where is the code and data linked to Martin’s paper?

- Who has cited Martin’s paper / code / data?

- Who has re-used Martin’s code and data?

- What grants has Martin brought in?

- What collaborators and what equipment has Martin been working with?

- Has Martin published in enough prestigious journals to get a bonus / tenure?

2.3 Efficiency, effectiveness and social value

Nick Petford on blockchain for procurement

“Blockchain provides a new way for organisations to engage with technology to reduce cost, improve speed and transparency and integrate social value” – Nick Petford, University of Northampton VC & CEO (read Nick’s article on blockchain for procurement in Efficiency Exchange)

How could this work? Let’s look at some examples:

- Martin’s student loan is automatically approved and tuition fees paid on confirmation of his place

- Martin’s institution tracks provenance of goods and services, e.g. through a partnership like Project Provenance or the Blockchain Alliance for Good

- Martin’s library fine is automatically deducted from his “eduCoin” account

- Martin decides to switch to a course at another institution – credit transfer takes place automatically

- What’s next?

A lot of people are exploring whether blockchain could help their project or service to work more efficiently, or looking at creating something which is wholly new and powered by blockchain. Whilst there are undoubtedly huge opportunities, there are also a number of traps for the unwary. Coin Sciences CEO Gideon Greenspan has written a great article on avoiding the pointless blockchain project, which I have summarised in the following bullet points.

In short, your proposed use of blockchain:

- Must be a database – think in terms of adding new transactions and reading the history of previous transactions. It’s not a file store!

- Must have multiple writers / updaters – if there’s only one updater, you could just use a conventional database

- You don’t trust the folk updating the database – if you do trust them, you could just use a conventional database and grant them access

- You don’t need a trusted intermediary to vouch for updates / updaters – i.e. updates are permissionless. If you rely on a trusted intermediary then you could just a conventional database and grant them access

- Transactions are often dependent on each other – this is how the true potential of blockchain is unlocked, e.g. think about degree certificates only being released on successful completion of exams and coursework + payment of outstanding fees and fines

- Database contains rules for assessing the legitimacy of transactions – this is the underlying principle for Ethereum’s smart contracts

- Database contains a mechanism for conflict resolution –relying on external data or services for this can be problematic as any external interfaces need to produce the same results no matter which blockchain server node is contacting them, and some operations (like several of the steps involved in buying a house) can’t inherently be repeated by multiple blockchain nodes without unwanted consequences

- Information / asset in database can be drawn down – i.e. who stands behind the information represented on the blockchain, for example a funds transfer, an exam board or university, government property or land registry

You will also recall the key blockchain concepts that Audrey Watters introduced – an unalterable, semi-public database, that multiple untrusted parties can add entries to. As part of the embracing of blockchain by Wall Street and central government, a number of these pillars are being chipped away at. For example, Accenture recently won a patent for their work on making the blockchain editable using the wonderfully named “chameleon hash”.

Whilst the Bitcoin blockchain is inherently a public record of transactions, a number of companies are now offering private blockchains, and “permissioned” blockchains that only certain entities can update. Whilst these developments are sometimes frowned upon by blockchain pioneers, it may well be that they provide the certainty and oversight that is required to make blockchain truly mainstream.

There are a number of issues with Bitcoin derivatives that make mass adoption problematic – in particular the requirement for an underlying virtual currency which must be mined using a compute (and hence power/cooling) intensive process. Alternatives to this “proof of work” approach are starting to emerge in next generation distributed ledger technologies like the Hyperledger system which underpins Sovrin self-sovereign digital identities.

Transaction time itself can also be a huge problem – Bitcoin is currently only able to process around 4 transactions/second, with Ethereum somewhat faster at around 20 transactions/second. This compares unfavourably with PayPal at 200 transactions/second. For us to be able to use virtual currencies like Bitcoin and the underlying blockchain technology all across our daily lives then performance will have to be significantly improved. This is an active research topic at present.

Finally, while we having been talking about blockchain as a “database”, it isn’t suitable for storing documents or digital media onto, because each blockchain server node has to store a copy of the entire blockchain. Blockchain applications typically manipulate references to data held elsewhere, such as Digital Object Identifiers for research papers. It should be noted that there are also parallel efforts to create distributed file storage systems, like the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS).

Conclusions

There are plenty of potentially transformational applications for blockchain or distributed ledgers more generally in research and education. However, we are still at the “28k modem” stage, comparable with the early web of the 1990s, and there are many traps for the unwary.

Most importantly, take care to avoid the pointless blockchain project – right now there is a lot of “blockchain washing” to make an unattractive project seem more appealing. If in doubt, use Gideon Greenspan’s test to help you understand whether blockchain is truly necessary, or simply adds an extra layer of complexity and new failure modes.

Potential collaborators around blockchain in research and education are global as well as local. In this day and age we can collaborate on a global scale around digital technologies just as easily as we can with our neighbours, so we can all drive on the same side of the road and there’s no need to have the equivalent of our own special UK electrical plugs and sockets! And there are a large number of open source Ethereum applications that you can build on.

If having read this report you are interested in pursuing blockchain further, we’d love to talk to you – so please do get in touch. You might also want take a look at the presentations at the recent Blockchain in Education conference, and this report from the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission, which are a good round up of the state of the art right now.

Blockchain research from the Open University, screenshot from http://blockchain.open.ac.uk

We are collaborating with the Open University on their Open Blockchain R&D project, which has set up a testbed blockchain network for modelling research and education use cases.

Finally, do let us know what you think of this report by leaving a comment. be sure to read our other horizon scanning reports and keep a look out for new material – we aim to put a new report out every couple of months.

About Jisc

We are a not-for-profit company owned by and serving the HE, FE and skills sectors in the UK. There are around 18 million users of our shared services like the Janet network, eduroam, JiscMail, and our shared data centres. We also do a number of national deals with IT vendors and publishers, such as Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Elsevier and Springer. Our other key activity is to provide advice & guidance to the sector on digital technologies in research and education.

My role at Jisc is to lead a small group which is exploring the potential in research and education of emerging technologies like Virtual and Augmented Reality, machine learning and brain computer interfaces. We help institutions to devise and implement their digital strategies, and to build the evidence base around new technologies.